The vision of Roam Ranch is to turn almost 1,000 acres of central Texas land back into the kind of place that can support an ecosystem instead of the “unsalvageable,” industrially farmed land the co-owners, husband and wife Taylor Collins and Katie Forrest, had purchased.

Taylor said it looked empty, like the face of the moon when they had first arrived. On the day we visited, tall wild grass rustled, beauty berries and fig trees blossomed, birds of prey swooped overhead.

Before my assignment, I researched a bit about bison evolution—where they came from and what made them unique. I learned that there are only two living species of bison: the European Bison and the American Bison.

I learned that, despite people’s insistence on calling them American Buffalo, American Bison are only distantly related to any kind of buffalo. One give away between the two is that bison have a giant hump on their necks and upper backs. Buffalo do not. This hump is made of elongated vertebrae which are covered in powerful neck muscles. This allows American Bison to use their heads as a snowplow in the winter—pushing back layers of snow and revealing nutrient rich grasses.

We got there early, parked in the grass, and walked up the dirt road that led to the field house, where people were waiting for things to start.

Our soundtrack was conversation—who we are, who we’ve been, who we might become. What we’ve learned, like that bison can stand within two minutes of birth and run within seven. They must—born prey, they have a generational muscle memory of fleeing.

In the days prior, I told my neighbor Lynda I was nervous. We stood by the mountain laurel in my driveway for a conversation that sprawled from New Zealand, her grandmother popping out back to grab a hen for dinner, to Lynda’s distant memory of learning how to de-feather between garden beds stacked with more okra than any human could want to endure. My own childhood was sealed in cans–green beans, peaches in light syrup, the metallic tang of factory freshness. My tie to the land was convenience.

How quickly we’ve disengaged from the cycles that sustain us.

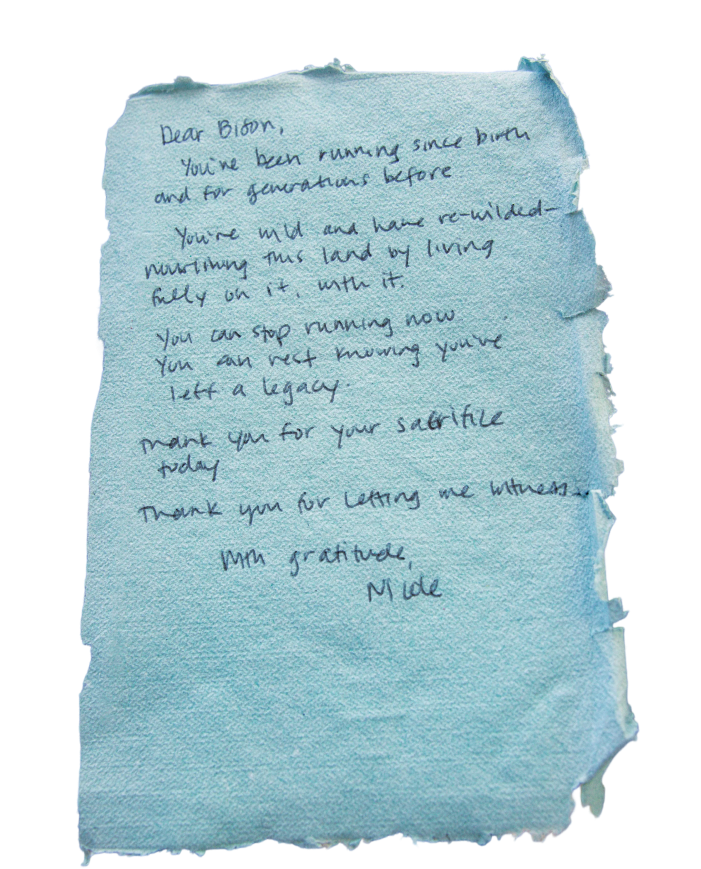

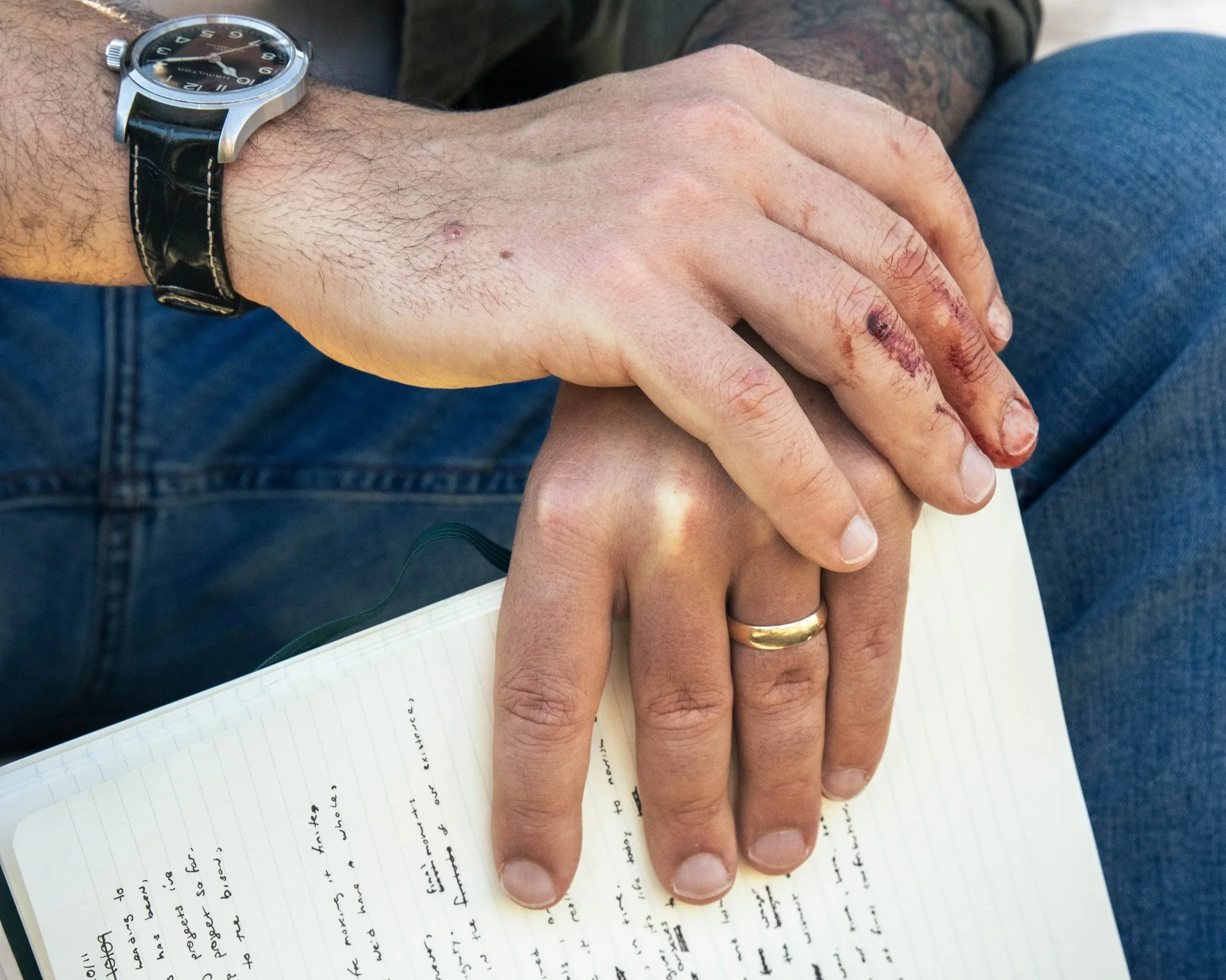

The group of us—farmers, writers, hunters, generally interested folks from Central Texas—were on the property that day to see the whole process, the entire cycle of life from bison grazing in a field to meat on a dinner table. Taylor and Katie had prepared us for the experience by encouraging us to write letters to the bison and take some time to sacrifice beforehand.

Everyone fell to a hush, and the engine of the pickup switched off so that the only sound was the putter of the gator’s motor as it worked the angles of the herd, and the soft, steady rustle of the bison as they moved to get out of its way.

Miles deep down ranch roads, we gathered in a surreal semi-circle near the smotherweeds as the ranchers told the story of the land.

Once industrially overused, tilled without rotation, grazed without rest, the land was written off as unsalvageable.

When the owners of the ranch purchased their parcel, it was nine hundred acres of industrially farmed, drained, and desolate land. After just eight years under their stewardship, the ranch is unrecognizable, and now functions as a fully integrated ecosystem. They took a hands off approach, not seeking to optimize each individual variable, but rather provide the land with the natural ingredients it needed to heal itself.

The ranchers explained that bison contribute directly to the ecology by improving soil health.

Not only with their manure, but with their spade-shaped hooves.

These are excellent tools for breaking up hard-packed soil, allowing for the scarce rain water of Central Texas to soak into the ground and introducing insects and microorganisms that help regenerate nutrients in the soil.

Here and there ranch hands talked with chefs as they all moved things from one truck to another. Under the big oak trees that dominated the space, tables had been laid out for the work. And everywhere, there was the anticipation that comes before something good, but difficult.

Taylor gathered everyone in a sunny part of the road that snaked between the field house, the sprawling oak trees, and the big tool shed, and prepared us for what was to come.

He told us how the animal had lived its entire life on this ranch. How in doing so, it helped the ecosystem, its hooves tilling the land while its manure spread the seeds from one place to the next, transforming the grass into vital nutrients to be worked back to the soil.

Now, it faced its final transformation into something that would sustain us, he said. And he made a point of saying that it would go quick, surrounded by family, with its favorite food in its mouth – a sudden expansion of consciousness and energy.

Each part of the bison would go to something.

Each part of the bison would go to something.

the caul fat to a regenerative farmer,

leg meat to the hunters who knew how to make it into rich stews,

the skin of the testicle for a coin purse,

the hooves to be made into bolo ties,

the heart for tartare we would eat right then and there.

I knew I was going to watch a bison die. Eight days’ notice was just enough time for the knowing to settle under my skin, to echo each time I ate lunch with my colleagues, fed my hens, stepped into the quiet after bedtime.

I’d been invited to a harvest at a regenerative ranch in the Texas Hill Country.

Harvest, not slaughter.

I carried it in my lungs.

How do I witness death?

The chosen bison was a three-year-old bull, born in drought, one of a handful to survive a preventable sickness. His death would feed the soil, feed us.

We passed the rifle cartridge around. The ranchers told us this would not be a moment for I’m sorry, but for thank you.

We watched from the shade of a live oak.

The shot. The bison dropped. The collective breath released.

I do not know quite how to explain to you what it was like to hear the crack of the bullet and know the bison had been hit. Or how it felt to stand in the hot sun and listen to Taylor read a letter of gratitude to the bison. Or what it was like to crouch down and put all of my fingers in the fur of the bison’s face, its eye already beginning to cloud. I do not quite know how to explain it because how does one explain the chasm between life and death?

The herd did not run away. They encircled the fallen bull lying on the ground, and mourned as a community. The ranchers told us this was how the herd processes the sacrifice of their brother without fear. They were not afraid because they did not evolve in tandem with humans and guns, and therefore perceived no threat.

There was no hint before the crack of the rifle shot. The herd was simply moving one moment, still for a heartbeat, and moving again a moment later.

Taylor had told us that the bison had their own way of acknowledging the loss of a member. And though I couldn’t quite see it all from where I sat, I had an idea of what they were doing in those minutes after the shot.

So long before the earth was tamed and taught,

there was a race between two wild brothers.

Their breasts did bare the reckonings of pride.

a man was one, strong beast the challenger.

The victor would be known throughout the lands,

as a great protector and worthy king.

The loser would concede with noble grace,

living his days in service of his brother.

When crickets sang the two began with haste,

an ancient wind lent credence to their contest.

They ran into a future unforeseen,

one that would change the lands they called their home.

They bound fair fields of bluestem and red rye.

They leapt grand mesas of sandstone and shale.

They raced until the sun dipped his face below,

and after his wife revealed hers in the night.

The hearty beast’s strong hooves did crack and ache.

Mouth of man foamed from unbroken running night.

Their hides blistered from rays of cloudless sky,

and tears carved muddy rivers down their cheeks.

The man was nearly lost, his legs weary,

although he had deceptions yet to play.

He grabbed ahold his brothers rugged back,

hoisting himself upon the mighty hump.

The noble buffalo did thrash and rear,

but he could not shake his brother above.

Together they galloped into shrouded night,

one final time they rode as equals on.

An end was near the race surely complete,

the man pulled himself atop the beast’s great head,

wily arms and legs both coiled tight with force.

the buffalo bound forth with vigor and haste .

Though not a moment left man burst forth from,

atop his brother’s head, with arms stretched out.

Man seized his victory through guile and gall,

a steward to his brother he would become.

I am grateful for the way you have brought these fields back to life, how your ancestors fed our ancestors, how your body will feed me and so many others.

Since you are to die today to feed the animal that is my body let it be marked by these words, let it be worthwhile, let it be observed. I bring to you my attention and my spirit.

Thinking of you in the field—which is the image that comes to me, sun on a soft brown face, wild grass flattened by the wind—I am reminded of my own animal-ness. My lungs that fill with air, my muscles that stretch and ache, the fat on me that moves when I run. I am reminded more of the ways you and I are alike than I am of the ways we are different.

Some things you just have to experience, because they come from the time before words. And when you do, you shouldn’t try to write about them unless you’re sure you can do it right.

Roam Ranch brought life back to a system that science had killed.

Under a few shady trees, we butchered the animal—or really, a few Roam Ranch employees butchered while we watched and learned.

We passed around the heart, smooth and heavy. A rancher breathed into the bison’s lungs, reanimating them to full bloom. I tasted raw liver dusted with pink sea salt, heart tartare on sourdough. I didn’t look away.

The settlers, on the other hand, used to kill the bison, take its hide and its tongue and leave the rest to rot. Those are the people I come from, my father’s family having been in the United States since the Revolutionary War. I do not come from a rich tradition of Native people. I am much more closely related to the men who yelled yeee-hooo! as they slaughtered bison after bison for leather that could make them money and be turned into machine belts back East.

The tongues were canned and shipped out or served as delicacies, covered in sauces in restaurants with silverware and china plates. The men who killed the bison did little of the work of turning the bison into food themselves, left so much to the vultures. It’s showy and wasteful, this kind of food.

When the bison was taken from the field, a puddle of garnet blood left behind, its full three hundred pounds hanging from a tractor, something shifted in me a bit. The giant question of life and death turned into a much more approachable question about what we would do to turn this bison from animal to food.

The entire herd was a part of the harvest that day, and so were we. We became part of a system. One composed of a billion living breathing parts that cannot be separated, or studied, or understood in isolation.

The work now is to tend what remains. To give purpose to what we can, to compost what’s overused, to make room for what’s next.

My mind tried to find a frame: the bison as crucifix, Achilles-held, a flash of poetry from undergrad, the strange ways we metabolize awe. How to fit this into the world I knew? How to not look away, not escape from witnessing this shift, this sacrifice.

The bison’s blood tasted like grass, faintly salty, almost clean.

There was still sweet grass in the mouth of the bison when we removed its grey tongue. All of that mild plant turned into organs and muscles bathed in that sweet, mild blood. It was delicious. It was rich. It was profound.

I felt a duty to be a more engaged consumer of what I take in. I felt a deep connection to the energy of all the animals that had ever fed me. I felt a oneness. I understood that sometimes I will be the one with my fingers in the neck of the downed animal and one day I will be the downed animal.

The morning after the harvest I woke up early, restless.

A small inconvenience with my pharmacy caused me to dissolve into tears that I couldn’t stop. It was not about the pharmacy. Tears like that never are. On the farm, the man butchering the bison had said, death is normally in a box over there, tied up with a neat little bow. Today you’re going to need to bring that box over here and open it up. Turns out the bow is a little harder to tie back on.

Thinking of you in the field—which is the image that comes to me, sun on a soft brown face, wild grass flattened by the wind—I am reminded of my own animal-ness. My lungs that fill with air, my muscles that stretch and ache, the fat on me that moves when I run. I am reminded more of the ways you and I are alike than I am of the ways we are different.

Bison followed me through the days afterward—a giclée in my dentist’s office, a threadbare stuffed animal at school drop-off, a fine-lined tattoo on a man’s calf at the gym.

What happens when we stop numbing and look closely at what’s hidden? When we let curiosity replace avoidance? When we root exactly where we are.

Creative Director

Zachary Solomon

Field Guide Writers

Ethan Brooks

Katie Rice

Nicole Stump

Ashley DiMarco Ph.D.

Photography

Stephanie Saldivar

Website Design

Luree Art + Design

Thank you to Taylor and Katie Collins at

Roam Ranch